Ancient Hallucinogens of the Andes: Earliest Evidence of Ayahuasca Use Discovered in Peru

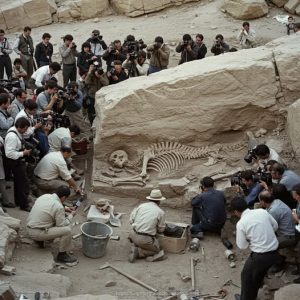

Archaeologists have uncovered what may be the earliest known evidence of ayahuasca use in human history — a discovery that sheds new light on the spiritual and ritual practices of ancient Andean civilizations. The finding comes from the analysis of hair samples taken from 22 mummified individuals found in southern Peru, near the ancient Nazca religious center that flourished around 100 B.C.

The mummies, remarkably well-preserved by the region’s arid climate, were examined using advanced chemical techniques to detect biomarkers of psychoactive plant compounds. To the astonishment of researchers, several samples contained traces of Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis — the two main ingredients in ayahuasca, a potent hallucinogenic brew still used today by Amazonian shamans to induce visionary states.

A Window Into Ancient Rituals

The discovery not only pushes back the known use of ayahuasca by nearly two millennia but also reveals how ancient spiritual traditions in the Andes may have intertwined with ritual intoxication and sacrifice.

According to Dr. Valeria Montes, the lead archaeochemist on the project, the presence of these plant compounds indicates that the individuals were likely involved in religious or ceremonial practices that required altered states of consciousness.

“This is not casual drug use,” Dr. Montes explained. “These plants were powerful and sacred. Their use was controlled, ritualized, and deeply symbolic — likely reserved for priests, shamans, or sacrificial participants engaged in communication with the divine.”

From Ayahuasca to Coca: A Cultural Shift

While the earliest mummies — dating from around 100 B.C. — revealed traces of ayahuasca-related compounds, later individuals in the same burial site showed chemical signatures of a different substance: coca alkaloids, derived from the leaves of the coca plant (Erythroxylum coca).

This shift, scientists believe, may mark an evolution in ritual practices, particularly surrounding human sacrifice and ceremonial devotion.

The Nazca culture, known for its iconic geoglyphs etched into the desert plains, was deeply spiritual, emphasizing fertility, water, and cosmic harmony. Yet archaeological evidence — including trophy heads, ceremonial knives, and painted pottery — suggests that human offerings were an integral part of maintaining balance with the gods.

Dr. Montes and her colleagues propose that the transition from hallucinogens to coca might reflect a transformation in religious ideology — from ecstatic trance communication with deities to sustained, alert states suited for labor-intensive ritual acts.

“Coca would have provided endurance, focus, and energy rather than visions,” she noted. “This could represent a move toward rituals emphasizing physical sacrifice over spiritual revelation.”

The Science Behind the Discovery

To reach these conclusions, researchers used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to identify molecular residues in ancient hair samples. Unlike bones or soft tissue, hair retains biochemical markers over long periods, effectively preserving a timeline of an individual’s ingestion habits.

In some mummies, the combination of mescaline-producing plants and ayahuasca ingredients suggests a sophisticated knowledge of pharmacology, indicating that these early peoples understood the synergistic effects of multiple psychoactive substances.

Such findings challenge the long-held belief that ayahuasca use originated exclusively within the Amazon basin. Instead, it may have formed part of a pan-Andean spiritual tradition, linking highland and lowland communities through shared ceremonial plant use and cosmological beliefs.

Echoes of an Ancient Psyche

The discovery resonates beyond archaeology — touching on anthropology, medicine, and spirituality. Ayahuasca remains a cornerstone of indigenous shamanic practice in South America, used to access visions, confront mortality, and seek divine guidance.

To find traces of it among mummified remains over 2,000 years old connects modern practices with an ancient lineage of human curiosity about consciousness and transcendence.

“These people weren’t just experimenting with nature,” Dr. Montes reflected. “They were exploring the boundaries of the human mind and spirit. It’s a reminder that the desire to reach beyond the material world is as old as civilization itself.”

A Legacy Written in the Body

As the study continues, archaeologists hope to uncover more evidence linking plant use to specific ritual sites and burial customs in the Nazca region. The findings promise to deepen our understanding of how psychoactive plants shaped belief, identity, and even mortality in the ancient Andes.

For now, these strands of hair — delicate, silent, and ancient — tell a story more vivid than any inscription: a story of humans seeking communion with the divine through the mysterious gifts of the Earth.