A new genetic study is rewriting what researchers know about early human migrations in East Asia, showing that the prehistoric Jomon people of Japan carried far less Denisovan DNA than any other ancient or modern population in the region. The findings suggest that at least one early lineage of modern humans in East Asia either never encountered Denisovans or interacted with them only rarely.

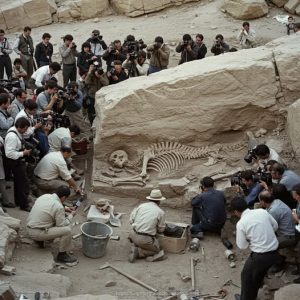

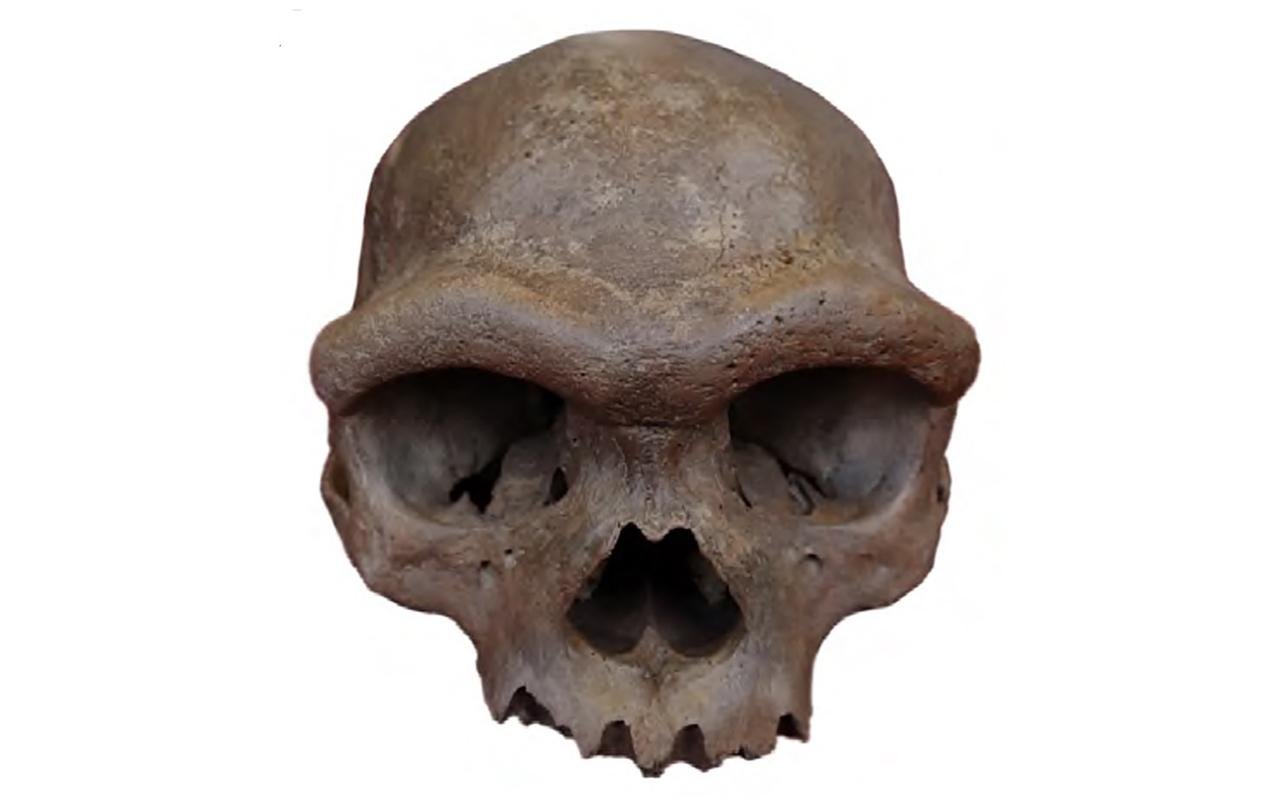

The 146,000-year-old cranium of an individual with Denisovan DNA discovered in China. Credit: Fu et al, Cell (2025)

The 146,000-year-old cranium of an individual with Denisovan DNA discovered in China. Credit: Fu et al, Cell (2025)

The research, published in Current Biology, analyzed hundreds of ancient and modern genomes to trace how DNA from the Denisovans—an enigmatic group of archaic humans that lived in Eurasia between 200,000 and 30,000 years ago—became dispersed among different populations. While today Denisovan ancestry appears in many communities across East Asia, Oceania, Southeast Asia, and the Americas, it is unevenly distributed and genetically complex.

To untangle this pattern, researchers analyzed the genomes of 115 ancient individuals from East Asia, Siberia, the Americas, and West Eurasia, as well as genetic data from 279 modern-day humans. This large dataset allowed the team to reconstruct when different groups of early Homo sapiens interbred with genetically distinct Denisovan populations.

One of the clearest signals came from ancient mainland East Asians: people who lived in parts of China and Mongolia had the highest levels of Denisovan ancestry anywhere in Eurasia. Their DNA revealed contributions from multiple Denisovan groups, and indicated that the admixture events occurred before the Last Glacial Maximum, roughly 26,500 to 19,000 years ago. In contrast, ancient Western Eurasians showed very little Denisovan heritage, suggesting that the contact in this area was highly limited.

Among all the populations studied, the Jomon people of prehistoric Japan were an outlier. Genetic material from individuals who lived between 16,000 and 3,000 years ago showed remarkably low Denisovan ancestry—much lower compared to the levels of ancient mainland East Asians and even below proportions seen in present-day East Asian populations. One Jomon individual who lived nearly 4,000 years ago carried only a fraction of the Denisovan DNA found in modern Japanese.

These results point to a deep East Asian lineage that acquired little, if any, Denisovan ancestry. This lineage may have taken a different migration route into East Asia, according to the researchers, or reached regions where Denisovans were extremely sparse. The team notes that Denisovans were likely not evenly distributed across the continent, making encounters highly variable between groups.

Successive migrations into the islands are likely to have changed the genetic landscape of Japan. By the Kofun period (CE 300–710), large-scale movements from the East Asian mainland introduced more Denisovan ancestry into the archipelago and gradually diluted the earlier Jomon genetic profile.

Still, some major gaps in the timeline remain. For example, modern humans are known to have inhabited Japan at least as far back as 32,000 years ago, but the oldest Jomon genome analyzed so far comes from an individual who lived around 9,000 years ago. How the 23,000-year gap between these two dates is filled with ancient DNA, the researchers say, will help elucidate how early populations spread across East Asia and how their encounters with Denisovans shaped the genetic landscape seen today.